What does it mean to be human, created in the image of God? What of race, creed, and religion? Who has the final say in protecting people, their rights, and possessions? Our past experiences and those of our ancestors will certainly color our response to such profound questioning. Throughout history, the resilience of the human spirit has proven itself to be lion-hearted, no matter our history or heritage.

“We need to help people know what happened, that it could happen to anyone, and that it must not be repeated.” says Ray Locker, communications director and strategist for the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. He works to help preserve and memorialize the Heart Mountain WWII Japanese American Confinement Site located between Powell and Cody, Wyoming.

History Lesson

As World War II raged on, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 ordering 120,000 Japanese Americans residing in California, Washington, and Oregon from their homes. In the fall of 1942, 14,000 people, two-thirds of whom were native-born American citizens, arrived by train to the confinement site at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. These people were deemed dangerous spies and saboteurs.

Bringing only what they could carry, they were assigned a family number and space in a tar paper barrack. Inside these crude structures hung a light bulb in the center of the room with a stove for heat standing in the corner. There was also a military-issue cot and blanket. (heartmountain.org) In the shadow of Heart Mountain, surrounded by barbed wire and guard posts, the harsh mountain and high desert weather conditions would expose these families to frigid temps in the winter and blistering heat in the summer. Most had come from more temperate climates and didn’t even have a coat to wear. The government promised a clothing allowance that was late in coming.

An obvious struggle for normalcy, internees did their best to keep their families close and recreate a sense of community. They established schools, a hospital, and a fire and police department. The Heart Mountain Sentinel, the camp’s newspaper, chronicled everyday activities as people worked their various roles from teachers to farmers, artists to musicians, attempting to maintain a semblance of productivity and purpose.

The 150-bed Heart Mountain Hospital was built and opened on August 28, 1942. The boiler chimney, reaching over 75’ high, still stands as a sentinel over the camp site today. The hospital, staffed by 150 employees included a white Chief Medical Officer and Chief Nurse, Japanese American physicians, nurses, aides, dentists, pharmacists, and orderlies. Some 182 people died at the camp from illness, injury and age. 548 babies were born there. And life forged on in this makeshift place called home.

As food shortages plagued the camp early on, James Ito, a recent college graduate in soil sciences, began to prepare the surrounding unfarmed lands. Though the land seemed desolate and unproductive, the internees farmed over 1,100 acres of lettuce, peas, napa cabbage, daikon radishes, carrots and cantaloupe, as well as managing hog and poultry operations.

Though the injustices of their situation fostered feelings of anger, frustration, and confusion, so too the strength of community and the bonds of family fostered an even greater hope. A hope which would be needed to prevail upon when released from the camp in early 1945. When these brave Japanese Americans left Heart Mountain they were given $25 and a train ticket to their chosen destination. Upon their return many had lost everything as homes, businesses, and savings were gone –seized or sold off in their absence.

They found themselves wanting to forget the pain and trauma of incarceration at the camps, but in doing so inadvertently helped America to forget also. Thus, the grants and endowments being offered in 2006 by President Bush to encourage and support the preservation and interpretation of such historic confinement sites. Many “children of the camps” are now being encouraged to speak up about their experiences to help “heal the trauma of imprisonment and free the next generation from the pain of silence”.

The human spirit does not give up so easily.

Song of Evacuation

A poem by: Shisei Tsuneishi, Fall 1942

Finally the day arrived.

With five thousand friends we left

Our flowered California

Crossing over deserts and states

To deep in the mountains two thousand miles away.

“Enemies” we are labeled

Though rightful citizens

Our children are.

In the wild world of war

And the vortex of its waves,

We are caught, like it or not.

In our heart there is fear.

But deep within, there’s a ray of hope

That shines and spreads like the sunshine.

The mercy of strange fate, indeed,

For us all.

In this desolate corner of Wyoming

Ten thousand beings entrust their lives,

Oh Heart Mountain, if you have heart,

Please show a proud and noble people

The way to our future.

Past and Present

Sam Mihara, a second-generation Japanese American, at the age of nine, was forced with his family to move to the Heart Mountain prison camp. When the war ended they moved back to San Francisco. Sam went on to attend Wilmerding High School, U.C. Berkeley, and UCLA where he earned engineering degrees. He became a rocket scientist and later joined Boeing to become an executive on space programs.

After retirement, he changed careers and in 2011 he became a national speaker on the topic of mass injustice in the United States. Mr. Mihara is a board member of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation as he informs educators, schools, libraries, government attorneys, law schools, and other organizations interested in his wartime experiences through public speaking of which he has been awarded the Paul Gagnon Prize as history educator in 2018. In 2022, Sam was awarded the prestigious honor, the Biennium Award for Education, from the Japanese American Citizens League. He has spoken to over 103,000 students of all ages in 450 speeches across the world.

Another Japanese American overcomer, William “Bill” Higuchi, who passed away on May 10, 2024 at the age of 93, was incarcerated with his family as an 11-year-old boy. He went on to become a pioneer in pharmaceutical sciences and was a professor at the universities of Michigan and Utah where he mentored hundreds of students from around the world. A loving husband and father, he pushed beyond the memories and trauma of the family’s confinement to touch many lives with his gifts and talents. His generous support went a long way in establishing the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. In later years he spoke of how he “made it in life and now his job was to share his story so it never happens to anyone again.”

The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation (HMWF) took a major step in preserving this history when it opened the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center in August 2011. Now recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a Smithsonian affiliate, it joins the Buffalo Bill Center of the West as only the second Wyoming museum with such honor and opportunity. Being chosen as an affiliate gives HMWF opportunities to collaborate with the Smithsonian with broader reach for educational programs, workshops, youth programs, and traveling exhibitions to name a few.

“Our world-class museum has attracted interest, both nationally and internationally, signifying the impact of the power of place.” says Shirley Ann Higuchi, daughter of William “Bill” Higuchi and chair of the Heart Mountain board. She has also authored Setsuko’s Secret –a poignant revelation and depiction of her parent’s story of incarceration, also expounding on her mother’s vision for a museum at the site of this former camp.

Recent Endeavors

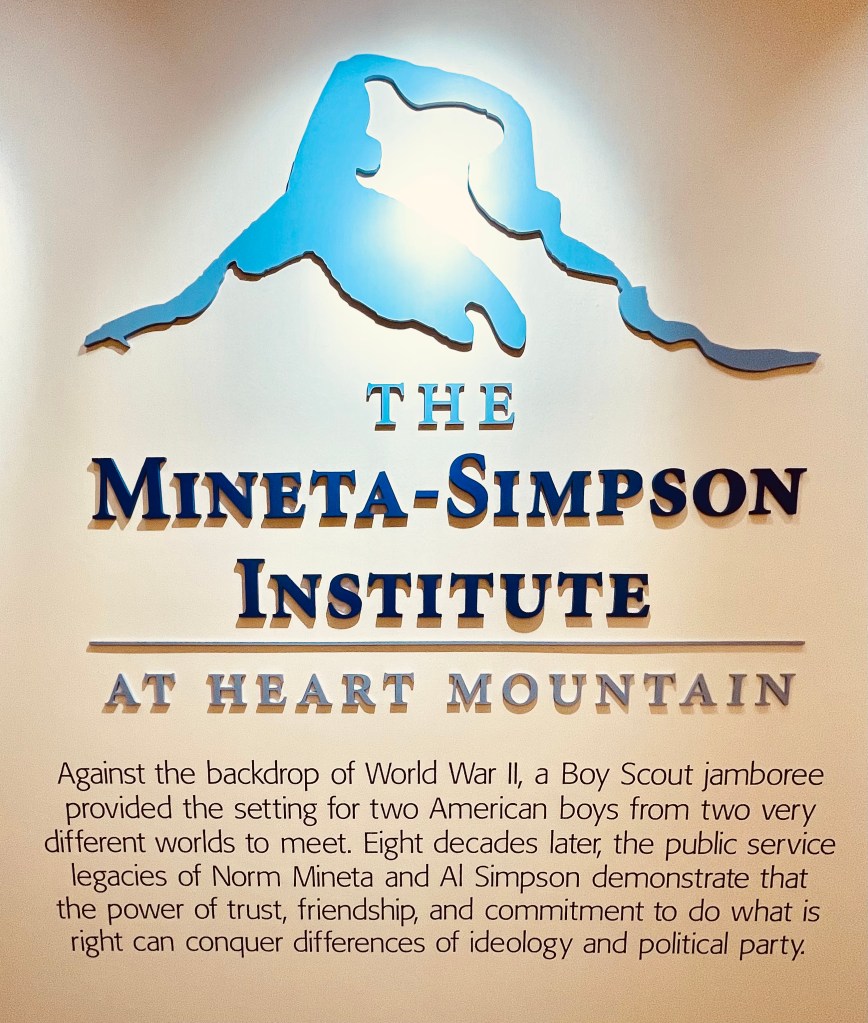

The Mineta-Simpson Institute celebrated its official opening in July, 2024. This permanent exhibit honors the lifelong friendship between Wyoming Senator Alan K. Simpson and the late Secretary Norman Y. Mineta. The two met in childhood as boy scouts at the Heart Mountain camp and have remained lifelong friends. Throughout their lives, Simpson and Mineta worked together to bridge political divides, advocating for civil rights and justice. The Mineta-Simpson Institute now serves as a space for dialogue on civil and human rights, offering workshops, lectures, and art exhibits to foster empathy, courage, and cooperation.

Recently, the National Park Service, Department of the Interior has granted $852,000 in restoring the original root cellar near the camp. “30,000 cubic feet of storage 300’ long by 35’ wide, this structure tells the story of determination, agriculture, and farming, and how people actually made lives for themselves here at Heart Mountain,” says Cally Steussy, manager, Heart Mountain Museum. The monies allocated are also good for surrounding communities by enlisting local builders and suppliers in the restoration efforts.

The Heart Mountain Interpretive Center offers ongoing tours between 10:00 to 5:00 daily. Visitors can learn about the heartfelt experiences of the internees and a broader context of the preservation of this dark chapter in American history.

Ultimately, the story of Heart Mountain WWII Japanese American Confinement Site is one of hope. It’s the story of people who, despite being torn from their homes and lives, rose above their circumstances. This legacy of resilience and strength must be remembered, cherished, and preserved to teach and inspire our children and grandchildren in the generations to come.

Visit heartmountain.org or call 307-754-8000 for more information.